Understanding JavaScript Objects (Part 1)

8 min read

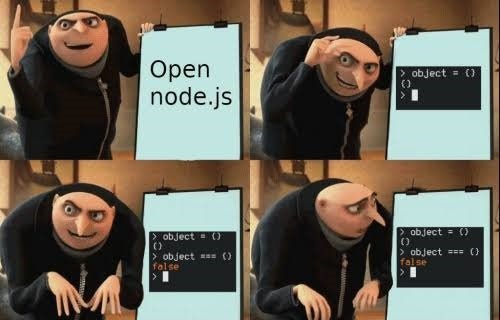

JavaScript has grown a lot in past few years. It has found its applications in almost every field. Because of this many developers try to learn JavaScript. Some of them are beginners while some of them have already been working on other languages like Python, C#, Java, C++. These are all Object Oriented Languages. The concept of objects in these languages are pretty similar. But, in JavaScript, objects behave very differently. This is the reason developers from another language face a lot of issues while dealing with objects in JavaScript. Also, this is one of the main reasons developers face issues.

Objects are key part of JavaScript and they work in a weird way. In this series, I'll try to explain how and why the objects behave the way they behave, how objects are actually created in different ways, prototypes and some more things. This was supposed to be a one huge post, but the topics that are covered will make it more confusing to read in one sitting.

In this post, we'll see why this has caused a lot of issues and how we can handle it using .bind() function.

Basics

Let's create a basic JavaScript object.

const sword = {

damage: 33,

hit: function () {

console.log(`You did ${this.damage} damage to the enemy`);

}

};

sword.hit(); // You did 33 damage to the enemy

When you call the .hit() function, on sword object, it will console.log() the string. In the string, it will see a variable this.damage. It will search for the variable in the object and it will find one with the value of 33 and will log the result as You did 33 damage to the enemy. This is an expected result. A basic object is declared in which a function references a variable of the object using this keyword and you get the value of that variable correctly.

Now let's try something different. Let's assign that function to a variable 🧐.

const sword = {

damage: 33,

hit: function() {

console.log(`You did ${this.damage} damage to the enemy`);

}

};

sword.hit(); // You did 33 damage to the enemy

const stolenSword = sword.hit;

stolenSword(); // You did undefined damage to the enemy

You did undefined damage to the enemy!? May be stealing a sword wasn't a great idea. But why is damage variable undefined here? We assigned the function to a variable and then called that variable. Yes, you can assign a function to a variable in JavaScript. This is because JavaScript is not only object oriented but also a functional language 🤷🏻♂️. And in functional programming, there is not concept of this. That's a whole another topic of discussion.

When we call stolenSword(), this is where the object oriented and functional nature of JavaScript clashes. When we re-assign a method connected to a object to a variable, it disconnects from the object. It is just a normal function now. The stolenSword function gets disconnected from the sword object (and functional nature of JavaScript comes into play) and this is the reason we get undefined for the variable damage.

An other way to explain it is look at the calling context. In the first example, the .hit() is called on sword object which has the damage property associated with it. In the second example, the .hit() method is assigned to stolenSword which doesn't have a damage property associated with it. The following code might help you understand better.

const stolenSword = function() {

console.log(`You did ${this.damage} damage to the enemy`);

};

stolenSword(); // You did undefined damage to the enemy

Here you can clearly see that stolenSword does not have any damage property and hence we get undefined. The this keyword does not refer to the context where it was defined, rather it refer to the context where it is called from.

Binding the Objects

We can achieve the initial behavior with the help of .bind() function. The .bind() function takes an argument of an object to which you want to the this keyword refer to. The .bind() function does not modify the original function, instead returns a new function. Let's see this in action.

const sword = {

damage: 33,

hit: function() {

console.log(`You did ${this.damage} damage to the enemy`);

}

};

sword.hit(); // You did 33 damage to the enemy

const stolenSword = sword.hit;

const boundStolenSword = stolenSword.bind(sword);

stolenSword(); // You did undefined damage to the enemy

boundStolenSword(); // You did 33 damage to the enemy

The .bind() function is called upon stolenSword and takes an argument of sword object. As you can see rather than modifying the same function it returns a new function that is stored in boundStolenSword variable. You can verify that by calling both of them, the stolenSword function will still return undefined but the boundStolenSword returns 33. The .bind() function forces to use sword object anytime this is referred by boundStolenSword function. Hence, we get the value of damage as intended.

A real world example of this could be as follows:

const sword = {

damage: 33,

hit: function() {

console.log(`You did ${this.damage} damage to the enemy`);

}

};

const button = document.getElementById('button');

button.addEventListener('click', sword.hit); // You did undefined damage to the enemy

button.addEventListener('click', sword.hit.bind(sword)); // You did 33 damage to the enemy

Using vanilla JavaScript we add an event listner to a button. Initially, as a callback function we've just passed the sword.hit. When the button will be clicked, the sword.hit function will be called but it will have the same issue we saw. sword.hit will be called by the global window object where all the event listeners are triggred. The window object does not have any reference to the damage property and we see undefined for it.

While in the second callback, we've explictly bound the this keyword to the sword object. Which means no matter where you call the sword.hit function from, the value of this will always be sword object.

More examples

We can not only bind the methods of an object but also normal function. We can use this inside a normal function and bind it to an object and it will refer this to that object.

function run() {

console.log(`Speed: ${this.speed}`);

}

run(); // Speed: undefined

As you can guess, speed will return undefined and you know the reasons. So what we do? We bind that function to an object that has a speed property.

function run() {

console.log(`Speed: ${this.speed}`);

}

const cheetah = {

speed: 120

};

const boundRun = run.bind(cheetah);

run(); // Speed: undefined

boundRun(); // Speed: 120

If this is what you expected, then you have got a good grasp of this and .bind(). Another way you can achieve this is placing the function right inside the object, because functions are values you can pass around, like strings, numbers, booleans.

function run() {

console.log(`Speed: ${this.speed}`);

}

const cheetah = {

dash: run,

speed: 120

};

cheetah.dash(); // Speed: 120

Nothing special happens to the run function. It is just passed to an object where when we call it, it has a reference to speed in the object because this is now the cheetah object. If we call the run function normally, it would still return undefined for speed. This proves that functions are not changed, they are just passed into objects and then refer to those objects. The dash and run functions are referring to the same function, not even a copy is made.

⚠ Warning! Confusing code ahead

This part will probably make you think for a while, but if you anticipate the output correctly, then you've understood the above things pretty perfectly. Also, never write this kind of code in real applications unless its absolutely necessary.

function run() {

console.log(`Speed: ${this.speed}`);

}

const animal = {

sprint: run,

speed: 50

};

const cheetah = {

dash: animal.sprint,

speed: 120

};

cheetah.dash(); // Speed: 120

After seeing this code, some people may say that cheetah.dash would result in Speed: 50. But remember, the animal.sprint is a reference to the run function. Although, calling animal.sprint will give Speed: 50 as the output, but calling cheetah.dash will still give Speed: 120 as output. Remember, there is just one function, run, that is been passed down as a reference and it will output the result as if it was passed normally into the object.

Summary

thisdoes not refer to the object where it is defined, but refers to the object from where it is called..bind()does not modify the original function, instead returns a new function withthisbound to the given object as the argument.

Note: This series is heavily inspired by Fun Fun Function's series on Object creation. The series may give you more insights as it has live coding examples.