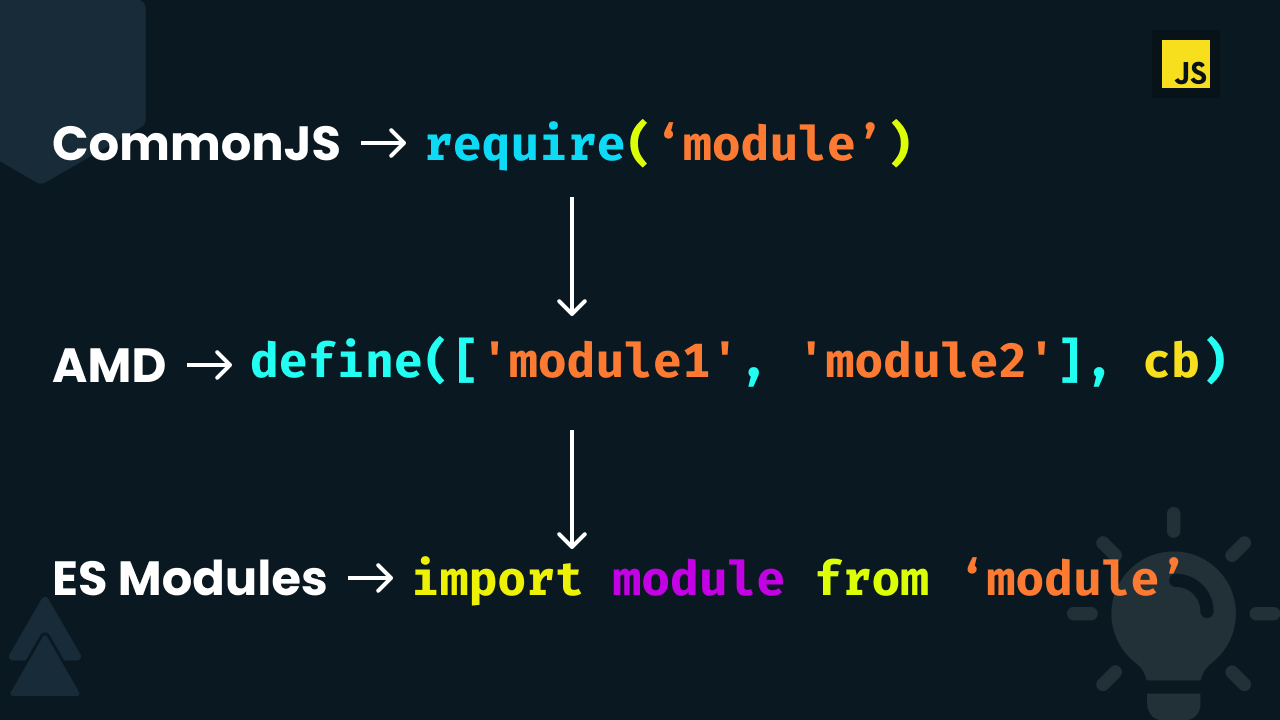

The Evolution of JavaScript Modules

9 min read

JavaScript as a language started off pretty small. It was used to add a bit of interactivity to the web page, validate inputs, handle events. These were small pieces of code that could fit into a single file and work independently. Few years passed and JavaScript is used everywhere.

- Websites / Web Applications

- Servers

- Native Mobile Applications

- Native Desktop Applications

- Web-based Games

- Machine Learning / AI

- IoT

- Flying Drones

- Everything 🤷🏻♀️

As the use of JavaScript was increasing, the code base also started to increase. Complex applications were made where having all the code in a single file was feasible. Developers needed a mechanism to spilt the code to make it independent and reusable. JavaScript didn't have built-in support for modules, but the community created impressive work-arounds. It was until 2015 when language-level module system was finally implemented in JavaScript.

CommonJS

CommonJS is a way to modularize JavaScript. The require function is used to import code from other modules, while the exports object is used to make the code available to other modules. Node.js used this standard to implement its own module system. There are not much differences between the CommonJS and Node.js implementation of modules. Node.js uses module.exports to export the code.

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

module.exports = add;

var add = require('./math');

add(5, 3);

Here, math.js file exports a add function that can be imported by any other file, in this case calculate.js, using the require function.

CommonJS insights🕵🏻♂️

When a require function is used to load a module, the process is broken down into 5 steps.

- Resolution - where the file paths are calculated.

- Loading - where the code in ongoing process is pulled.

- Wrapping - where under the hood the code wrapped in a function where the

require,exports,module,__filename,__dirnamevariables are made available (as shown below). - Evaluation - where the code is evaluated for any potential errors.

- Caching - where module is cached (if not already cached) for future use.

So the above math.js file will be converted as follows:

(function (exports, require, module, __filename, __dirname) {

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

module.exports = add;

});

CommonJS modules can be loaded dynamically. Meaning the require function can be used in an if condition to load the module whenever necessary. Hence, the evaluation of code is done dynamically and the errors are thrown at runtime.

if (operation === 'add') {

var add = require('./add');

add(5, 3);

}

But, there are few issues with this module implementation. CommonJS module is not aware of what functions or variables are exported until the module is evaluated. There is just one object that can be exported from a file. There is no concept of default and named exports. If multiple things need to be exported, they should be wrapped in an object and the object should be exported. Also, CommonJS modules are synchronous in nature. More require statements can block the execution of actual code. Browsers are not able to use these modules without transpiling. Because of this, another module system was born.

Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD)

AMD was built for browsers and was designed for asynchronous loading of modules. It has a define function that takes an array of modules as the first argument. As the name says, the modules are loaded asynchronously in non-blocking manner. The second argument is the callback function which is executed when all modules are loaded. In the callback function, you have access to the modules specified in the array.

define(['module1', 'module2'], function (module1, module2) {

module1.someFunction();

module2.someOtherFunction();

});

AMD is designed for browsers for better performance and better startup times. RequireJS is most popular implementation of AMD.

Till now there's no native support for modules in JavaScript. CommonJS and AMD tried to implement a module system but had some issues in its own. At the end of July 2014, TC39 had a meeting, during which the last details of the ECMAScript 6 (ES6) module syntax were finalized giving us built-in module system in JavaScript🥳.

ES6 Modules

ECMAScript 6 or ES6 or ES2015 gives us built-in support for modules in JavaScript. ES6 modules try to take the good parts from CommonJS and AMD and improve upon them. ES6 modules supports both synchronous and asynchronous loading of modules. ES6 modules can have named exports, that can be several per module and a default export, that is one per module. We can have both the default and named exports in the same module.

export const add = (a, b) => a + b;

export const sqrt = num => Math.sqrt(num);

export const square = num => num * num;

const multiply = (a, b) => a * b;

export default multiply;

import multiply, { add, sqrt, square } from './math';

// Use these methods here

Here, add, sqrt and square are named exports while multiply is the default export (for no reason). Named exports need to be destructured while importing. There are different ways to import and export which can be found here.

ES6 modules insights🕵🏻♂️

ES6 modules does not support conditional import and that is for a good reason (explained later). That means you cannot do this.

if (operation === 'add') {

import { add } from './math';

add(5, 3);

}

When an ES6 module is parsed, an internal structure called Module Record is created. This keeps the record of what functions or variables are exported at the time of parsing. This means when you use import { add } from './math', it creates a link between the imported and the exported add function. This helps to determine the imports and exports at compile time (static evaluation) before even having to execute the code and errors are thrown at compile time.

Although ES6 gives you less flexibility, it has several benefits.

Faster lookup

As the ES6 modules are static, you already know what content is exported. Compared to CommonJS modules, which are dynamically evaluated, you don't really know what is exported until the module is evaluated. This makes the lookup process slow. Knowing the exported content beforehand opens possibilities to optimize the code.

Variable checking

You already know what variables can be accessed in a module. This helps in spell checking the variable names. The linters like ESLint, JSLint, JSHint, etc. are used to check these types of errors before running the code. The modern IDEs and Text editors have plugins/extensions that help detect these errors while coding. This is possible because of static nature of ES6 modules.

Types

Everyone have heard of TypeScript, the superset of JavaScript. JavaScript is a weakly typed language. This has caused many errors that were difficult to resolve. TypeScript introduces types in JavaScript. TypeScript can do everything JavaScript is able to do, it just adds typing on top of it. This way the parser is able to detect the type errors at compile time that were difficult to handle in JavaScript.

Tree shaking🌴

This is where the static nature of ES6 modules shines. The true potential of ES6 modules is seen here. So what really is tree shaking?

Today, many JavaScript Frameworks and Libraries have adapted ES6 modules as their standard way to import and export. Although the import and export statements are not natively supported as of now, tools like Babel, Parcel and Webpack allow developers to use ES6 modules (there is a way to use ES6 modules in Node.js using .mjs extension, more info here).

Webpack is one of the most widely used module bundler. It is mainly use to bundle JavaScript files and make them usable in browser (it can also bundle assets like HTML, CSS, Image file, etc.). Over the year webpack is grown a lot and one of its most impressive feature is Tree Shaking.

Tree shaking in simple words is dead code elimination. Let's take a simple example to understand the basics.

export {

one: 1,

two: 2,

three: 3

}

import { two } from './file1';

console.log(two);

Here file1.js exports 3 different variables. But, file2.js only imports two variable. Webpack knows this (again because ES6 modules are static) and can safely remove the other two variables at production build.

But why ES6 and not CommonJS?

As ES6 modules are not natively supported as of now, people tend to use require statements. We already saw that the require statement can be used to dynamically import modules. They can be very useful at times, but, dynamic imports make it impossible for a static analyzer (like Webpack) to be very sure that the code that has been imported is actually called.

module.exports = {

assassin: () => console.log('Nothing is real. Everythin is permitted.'),

csgo: () => console.log('Rush B'),

farcry: () => console.log('Did I ever tell you the definition of insanity?'),

cod: () => console.log('Bravo 6, going dark!')

};

const getDialogue = () => {

// Calls an API to get which operation is to be performed.

// The API returns either 'assassin', 'csgo' or 'farcry'

};

require('./dialogue')[getDialogue()]();

When the getDialogue function is called it reaches an API that returns either "assassin", "csgo" or "farcry". Although we know that "cod" will never be return value from the API call, Webpack doesn't know it. Webpack doesn't know what the API may return. Because of this it will not be safe for Webpack to safely remove the cod function.

Earlier, we saw that ES6 modules does not support dynamic use of import, let's say in a function or an if condition. This gives Webpack a strong guarantee that the unreferred exports will never be called.

import { assassin, csgo, farcry } from './dialogue';

const games = {

assassin,

csgo,

farcry

};

games[getDialogue()]();

Since Webpack now knows that cod is not imported, it can safely remove it from the production build.

Note: We know that what values the API may return. If you are still importing cod knowing it won't ever be called, then you'll have hard time getting a job.

Conclusion

As ES6 is experimental, we can't really measure the performance difference between ES6 and CommonJS. I do suggest to use ES6 whenever and wherever possible. As it will become the standard, we'll see more great features like Tree shaking.